Warning: In the following paragraphs, I explore the pros and cons of an analytical mind, viewed through the cold, calculating lens of an engineer. I know this isn’t the tone you’re used to from me, but it’s the one that fits for this topic. I hope you find it enlightening or at least entertaining.

I’m finally getting on the airplane, relieved to be away from all the weird people in the terminal … Until I realize most of them just got on the plane with me. My eyes quickly catalog all the things wrong with every person and thing that I’ll be sharing the next six hours with. Why can’t she control her kids better? Why is he eating a King-sized candy bar when he’s got enough stored calories to fast for a year? Is that really a service animal?

The process is a little gratifying from a superiority perspective, but mostly it just makes me hate people. About three years into my engineering career, I started to notice this behavior in myself. As it turns out, I’m probably not that unusual.

It’s been a common joke in my life since college that engineers are scientifically proven to be cold heartless bastards. People cite articles like “Engineers are cold and dead inside, research shows” from The Register. It’s funny. We all laugh. But apparently it had become true for me, and based on my experience with many other engineers, I’d guess it’s quite common.

Self-Awareness Through an Engineer’s Lens

I started paying attention to my thoughts, hoping I could find a good person inside me after all. When was I most judgmental of people? Were my observations flawed? Were there good things I could look for in other people to try to balance my views?

The key for me came when I was hanging out with some friends. Not one of them was successful by any measure I might use. They had lame jobs, little education, poor health, and poor hygiene (as observed through the judgmental lens), but somehow, none of that mattered. I loved spending time with each and every one of them and couldn’t care less about their long list of perceived faults. What was different?

To me, the difference seemed to be creativity. That particular group of friends is very creative and inclusive in their gatherings. Every mundane detail of life could turn into a co-created, improvised, and ever-expanding comedy routine. I couldn’t help but join the fun, and when my mind was in that state, there was no judgement of other people. It seemed that spontaneous creativity turned off the judgement. Much later, I found an article on Cnet.com called, “Eureka! Engineers aren’t empathetic because they can’t be” that reinforced the idea that an analytical brain and an empathetic brain can’t be turned on at the same time. I must be on the right track!

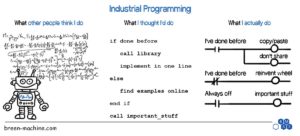

Pros and Cons of an Analytical Mind

The problem is that I can’t live most of my life in a state of spontaneous creativity. I’m an engineer in need of my analytical brain, which takes all the mental resources that creativity might use and bends them towards making sense of the world with hard, physical rules. More than that, I find that being able to see problems with things is incredibly valuable in my career. If I can foresee a problem with a design, I can improve it before the issue happens. Or if a machine is broken, my ability to spot defects helps me quickly root out the problem and fix it.

The problem with this mode of thinking, though, is when it inevitably turns towards people. People aren’t machines. Troubleshooting isn’t usually a good way to look at people. Everyone has problems of course, so there’s always something to fix, but after you go through the series of steps to understand what it is and prescribe the solution, it doesn’t fix the problem. More likely than not, they feel more self-conscious about the issue and less able to make the change required to fix it. In a machine, confidently declaring a problem, its cause, and a solution is wonderfully constructive. In a human, doing the same is often destructive.

Reframing Problems and Solutions in a Human Context

So given the pros and cons of an analytical mind, let’s look at solutions to the cons: How can an engineer improve their people skills? The first step is admitting to the problem. OK, I know, all your observations are correct. That’s not what I’m getting at. Recognize that telling people about their problem won’t fix it. Recognize that silently focusing on their problems will only put you in a bad mood. Think on that for a moment… Got it?

OK, now look for a way to get out of your analytical brain every once in a while. It’s good for you. It helps you see the other side of humanity and appreciate the humor in all those defects. And for the rest of the time, when analytical is all you can be, consider how most human problems are actually fixed: through leadership. Helping other people grow may be the highest calling a person can serve. This is the opposite of finding a flaw and shining the light on it; it’s about illuminating a person’s potential.

A common phrase in engineering is, “There are problems and there are solutions.” Let’s recognize that while solving problems is a great aim for machines, building on good things works a lot better with people.

About the Author

Jon is an engineer, entrepreneur, and teacher. His passion is creating and improving the systems that enhance human life, from automating repetitive tasks to empowering people in their careers. In his spare time, Jon enjoys engineering biological systems in his yard (gardening).